County Level Map of Beef Producers

Irina Zhorov

Under the brand Navajo Beefiness, farmers are meeting a speedily growing demand for their product. Is their success sustainable?

This story was originally published at High Country News (hcn.org) on June 17, 2020.

The land on the Padres Mesa Sit-in Ranch, in northeastern Arizona, stretched so vast and wild that it could be perspective-skewing, like shooting fish in a barrel to get lost in. Just Neb Inman effortlessly navigated his truck through a bounding main of blue grama grass, broom weed and sage. When he spotted a herd of cows, he hit the brakes.

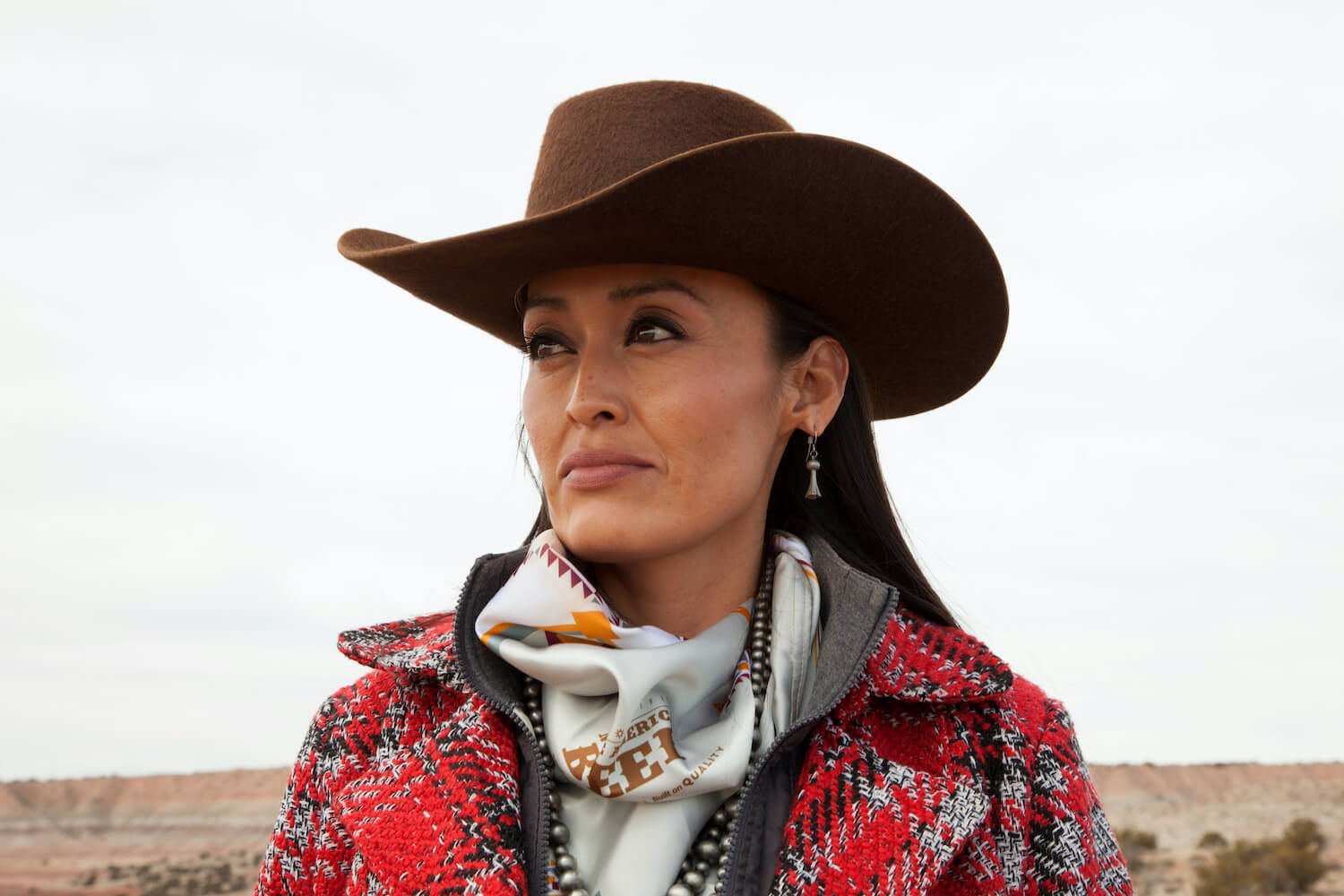

"She's a box of chocolates," Kimberly Yazzie said as she pointed at a stately heifer.

Nearly a dozen cows with week-old calves were bedded down in late wintertime fodder, all muted greens and gilt.

"She's pretty," Inman agreed.

"Information technology's taught if you have these things, you're going to keep to live a skillful life, you're going to practice great things and you're going to succeed."

Inman and Yazzie are trying to grow a beef make—Navajo Beef—with a community of Navajo families, Yazzie's included, who'd been relocated to this stretch of desert as part of the 1974 Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act. Most brought livestock during the move, much of it without papers, vaccines, or marketable genetics. Inman and Yazzie are helping them transform those animals into premium beef. It'due south a way to grow people's incomes in an area with few economic opportunities. The federal agency managing the relocation has bolstered their efforts, but after 40 years of being it'southward expected to shutter, threatening to dismantle progress.

Kimberly Yazzie was born on a rural expanse of the Navajo Nation, which stretches for 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. The broad-open land—Yazzie'southward closest neighbour lived most xxx miles away—lent itself easily to livestock. Yazzie's grandparents kept 80 sheep and more l cows.

"In the Navajo Diné traditional way of living the livestock is one of the main values," Yazzie said. "It's taught if you have these things, yous're going to proceed to live a skilful life, you're going to do great things and you're going to succeed."

Kimberly Yazzie's grandparents one time kept 80 sheep and more than than 50 cows. Afterward the 1974 Navajo-Hopi Country Settlement Act, the family unit was relocated to country that only allowed for twenty cows.

Irina Zhorov

Simply Yazzie'southward family lived on land disputed past the Navajo and Hopi tribes, a conflict instigated by federal policies from the 1800s. With the 1974 Navajo-Hopi State Settlement Human action, the federal government sought to resolve the disagreement in a fashion it ofttimes did when dealing with Indigenous peoples, by relocating them. Over decades, about 3,700 Navajo families left Hopi land and vice versa.

Yazzie's grandparents moved in the late 1980s. Yazzie'due south firsthand family followed in the late 1990s. Their new home was in the New Lands, a newly-created satellite of trust land, about 350,000 acres on the reservation's southern edge in northeastern Arizona. They occupied a house on a one-acre plot, in a cluster of other homes built by the Office of Navajo-Hopi Indian Relocation (ONHIR), a federal agency. "Giving up all of their open country space, information technology traumatized everybody," Yazzie said. "They withal shed tears for where they used to live."

"When will we ever be compatible with the Bilagáana, the white homo? Like, how do we create opportunity for our Native people?"

ONHIR too provided each family unit with a let to graze their animals on fenced range units. Ane permit covered about 20 cows. Much of the reservation, where cattle tended to roam freely and grazing quotas weren't strictly enforced, was overgrazed. The idea on the New Lands was to manage the land more sustainably.

But many relocatees weren't sold. Some, including Yazzie's grandparents, remembered stock reductions during the Groovy Depression, when authorities agents shot sheep in front end of their owners, purportedly to reduce overgrazing. Following the culling, the feds implemented the reservation'southward starting time permitting system. The programme, designed without local input, cemented distrust for such protocols.

Irina Zhorov

In 2009, ONHIR created the Padres Mesa Demonstration Ranch and hired Pecker Inman to run information technology.

The forced relocation, with its new rules, seemed taken from the aforementioned book. Yazzie said officials didn't properly explain the reasons for the permits, specially to elders. And then, when Yazzie's grandparents were forced to carelessness a majority of their animals, it made the move even more than painful. "Because you've already had to relocate these people and they were resistant in leaving and now y'all want to tell them how to manage their cattle and how to manage the country," Yazzie said.

—

Relocated animals arriving on the New Lands were a smorgasbord of different sizes and colors—blackness, white, red and tan—which indicated muddled genetics, unpredictable meat quality. People rarely vaccinated cattle or tracked nutrition.

"This area was known for low volume, depression quality, poor image and high-adventure livestock," Inman said.

Many Navajo producers didn't enhance animals every bit a article—rather, livestock served a subsistence role. At the sale barn, white buyers often took advantage of Navajo producers. A cow would fetch $500, hundreds of dollars below market rates.

The New Lands sits in Apache canton, 1 of the poorest in the U.Due south., with few job opportunities. Younger relocatees, who wanted to hold on to traditions but likewise to make money off the livestock, grew frustrated. The thinking, Yazzie said, was "When will we ever be compatible with theBilagáana, the white human being? Like, how practise we create opportunity for our Native people?"

Livestock quality improved. But there was a problem: Producers were nevertheless selling to middlemen at rock-bottom prices.

In 2009, ONHIR created the Padres Mesa Sit-in Ranch and hired Bill Inman to run it. The Ranch, pitched every bit an economic development initiative, would teach relocatees to professionalize their operations and care for the land. Inman organized branding days, taught people to administer vaccines and hired a handful of Navajo cowboys. He produced thick reports on forage wellness. The ranch as well leased out adept convenance bulls to refine herd genetics.

Livestock quality improved. But there was a trouble: Producers were still selling to middlemen at rock-lesser prices.

Yazzie was working as an agriculture instructor at the time, often using the Ranch's facilities for lessons. 1 day, while branding at the Ranch with her students, she ran into a man she didn't know. The human pointed to the animals grazing nearby; he said he wanted to buy and market place the cattle asNavajo Beef, to consumers increasingly interested in where their food came from and how it was raised. "I was mean to him," Yazzie recalled recently, laughing.

The herd the human had been eyeing belonged to the Ranch – in other words, to the federal government – not to Navajo producers. "So, you can't even telephone call information technologyNavajo Beef," she told him. She argued the characterization would appropriate the tribe's identity without benefitting its members. "Kids there were like, 'Ms. Yazzie, no more, just leave it, just leave information technology.' And I was similar, 'No, yous stand for what you believe in, this is wrong,' " Yazzie remembered.

The Padres Mesa Demonstration Ranch started equally an economic development initiative. Information technology teaches relocatees to professionalize their cattle operations and care for their at present limited land.

Irina Zhorov

The man'south proper name, she subsequently learned, was Al Silva, CEO of a big, Texas-based food distributor called Labatt Food Service. That evening he invited Yazzie to join Labatt, to start the characterization her manner, with Navajo producers. Since 2012, Yazzie has been recruiting producers whose animals come across Labatt's quality specifications.

To show what an eligible moo-cow looks like, Yazzie joined Anderson White, ane of Padres Mesa'south Navajo cowboys, on some errands. They drove by a neighbor's pasture where cows of all colors grazed on stubby forage. "That's where nosotros came from," Yazzie said, as White turned into a relatively lush ranch field. He stopped at a scenic watering hole, where a group of almost all-black cows mosied. "They look like great mothers," Yazzie swooned. She explained that she looks for livestock similar this: vaccinated, with square bodies, shiny coats, articulate eyes, majority English language breed, similar Black angus, of sufficient weight. For ranchers short of the marking she designs individual plans and works with Inman to make sure they progress.

Labatt buys the meat direct. They pay $0.04/lb over the market cost, plus a $35 bonus for animals that reach premium grades. On a good year, producers tin can now brand $900-$m per fauna. The meat is sold under theNavajo Beef label.

White'south personal herd has been part of the program since the beginning. "Carrying on the tradition just with better payment, pretty much," he said.

"We desire to make certain we take access to our traditional locally grown foods, right? That's kind of our overarching goal."

In 2012, Navajo casinos became the firstNavajo Beef customers. They pay a 25% premium for the meat; other distributors "wouldn't be Navajo beefiness and people, I think the team doesn't experience right nearly that," said Erik Mrdak, Executive Director of Food & Drink for Navajo Gaming. The story that accompanies the steaks is worth the actress cost "because ultimately it builds our business, and it builds the nation," said Navajo Gaming CEO Brian Parrish.

"We all dear information technology," said Benita Litson, who is Navajo and Director of the Land Grant Part at Diné College. Litson points to the tribe'southward food sovereignty ambitions. "We want to brand sure we accept access to our traditional locally grown foods, right? That's kind of our overarching goal." She's trying to copy the Labatt model with a small group of sheep producers. Somewhen, she wants Navajo businesses to butcher and distribute the meat, too.

Meanwhile, once-devalued Navajo beef has get sought later; the Navajo producers who had such a hard fourth dimension selling their cattle tin can't keep up with need. It'south even so a small, niche market place, but Yazzie has started to recruit producers from other tribes—Jicarilla Apache, Pueblo, Hopi—and broadened the label fromNavajo Beefiness toNative American Beef.

Families used to become just $500 for a cow, which was way under market place value. At present that Labatt buys the meat directly, producers tin can make $900-$1,000 per creature. The meat is sold nether the Navajo American Beefiness label.

Irina Zhorov

While many ranchers still want more than the allowable twenty cows, Yazzie said most now recognize the land'south limits. In Yazzie's own family, an uncle now has the allow her grandmother once held. He'south bred new genetics into the animals and they're office of Labatt's program, likewise.

"In a mode, the livestock was pretty much probably the affair that kind of brought a sense of pride back to [the relocatees]." Yazzie said today many producers feel thankful for what they've developed on the New Lands.

—

Despite its growth, Labatt'sNative American Beef label is not profitable or self-sufficient; Labatt and the ranchers rely on ONHIR to run Padres Mesa and fix fences, water tanks and windmills.

When the office was created, in 1981, its work was supposed to take v years. Now, about four decades in, ONHIR is slated to close. There's no timeline in identify or a plan for who, if anyone, will accept over Padres Mesa, which remains a universally liked ONHIR initiative. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Navajo Nation taking over have been floated as possibilities.

"In a way, the livestock was pretty much probably the thing that kind of brought a sense of pride back to the relocatees."

"We don't know, is the bottom line," said Larry Ruzow, ONHIR'due south legal director. "We know that nosotros'll be gone, and then information technology won't be us."

Silva and Yazzie don't have a plan for sustaining the label without Inman's and Padres Mesa'due south necessary aid.

Tardily 1 afternoon, Silva arrived at the Ranch, wearing a shirt withNative American Beef embroidered on the collar and a carful of ribeyes. He compared the label to baking bread, which needs but the correct conditions and ingredients. Without yeast, "it won't rise like information technology'southward risen," he said. "Then nosotros worked diligently to try and communicate that message. If the federal government is not here information technology goes back to before they were here: nothing."

Meanwhile, an hour and a half downward the road, at the Twin Arrows Casino'southward Zenith Steakhouse, a server told patrons stories about the families that raised theNative American Beef steaks they were nearly to order. The meat arrived on enormous oval plates, unadorned, its flavor as striking as the land that fed information technology.

woolnerexcerestint1993.blogspot.com

Source: https://thecounter.org/navajo-nation-ranchers-premium-beef-cattle-arizona-new-mexico-utah/